PROJECTS

Stalking a Killer: Ebola and the Hunt for its Source

By Pete Muller

In 2014 the world witnesses the largest outbreak of the lethal Ebola virus. Before surfacing in Guinea, and later spreading to Liberia and Sierra Leone, the virus was largely relegated to the remote forest regions of Central Africa where sporadic outbreaks were typically short lived and claimed a relatively small number of lives. It is thought that the scope of previous outbreaks was largely contained by virtue of the extremely remote and isolated nature of the environments in which they occurred. Hunters and other people who interact regularly with the forest and wildlife that lives there were typically the first victims. While no one yet knows where exactly the virus originates, researchers know that it lurks somewhere in the forest.

In December 2013, a mysterious illness emerged in the village of Meliandou, a small community deep in the forest region of southern Guinea. It first claimed a two-year-old boy, Emile Ouamouno who died after days of suffering fever and diarrhea. Days later, his mother also fell sick and died. The cases set in motion a wave of deaths in the village leaving members of the community in a state of panic. Traditional healers were called in to assess the situation and attempt to purge the virus which many villages thought was caused by witchcraft. Meanwhile, cases emerged in the nearby town of Gueckadou, along the borders with Sierra Leone and Liberia. Soon, cases emerged in both neighboring countries and the pace of transmission increased.

With West Africa’s comparatively sophisticated road networks and thus easier movement of people, the virus moved rapidly toward population centers where infect rates exploded. By August 2014, and the death toll reached into the thousands, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak and international health emergency. International aid organizations rushed to help the affected governments, whose institutions and response capacity were exceptionally weak, to bring the outbreak under control.

Once the virus reached the densely populated capital cities of Freetown, Monrovia and Conakry, the situation spiraled out of control. Governments issued emergency orders to stop all traditional funeral practices as contact with the bodies of Ebola victims was almost certain to pass the virus. Traditional bereavement practices were severely disrupted and the social fabric of the countries was strained. Non-essential public gatherings were also prohibited. The outbreak took a heavy toll on West African economies and even those who were not affected directly by the virus were suffering severely.

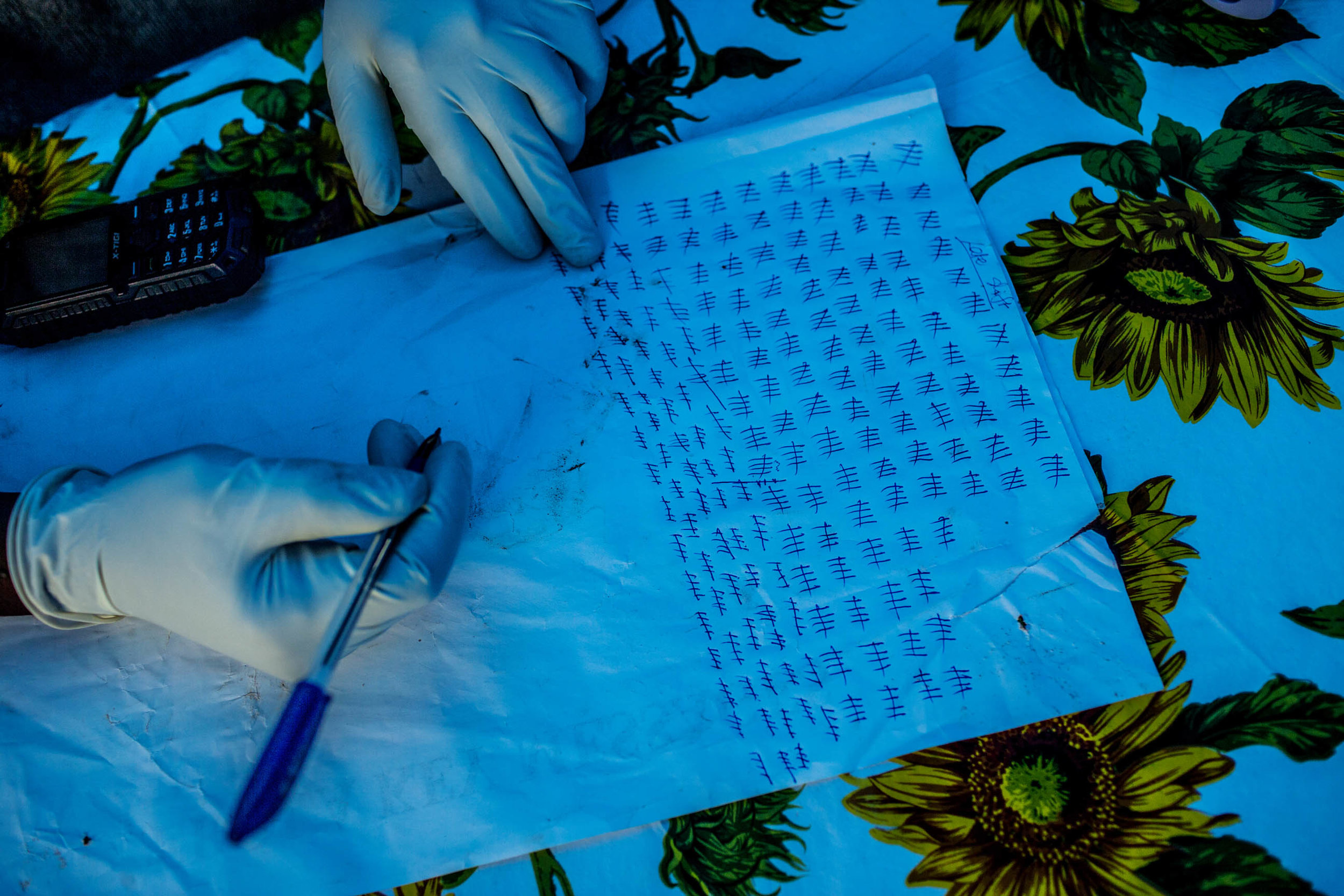

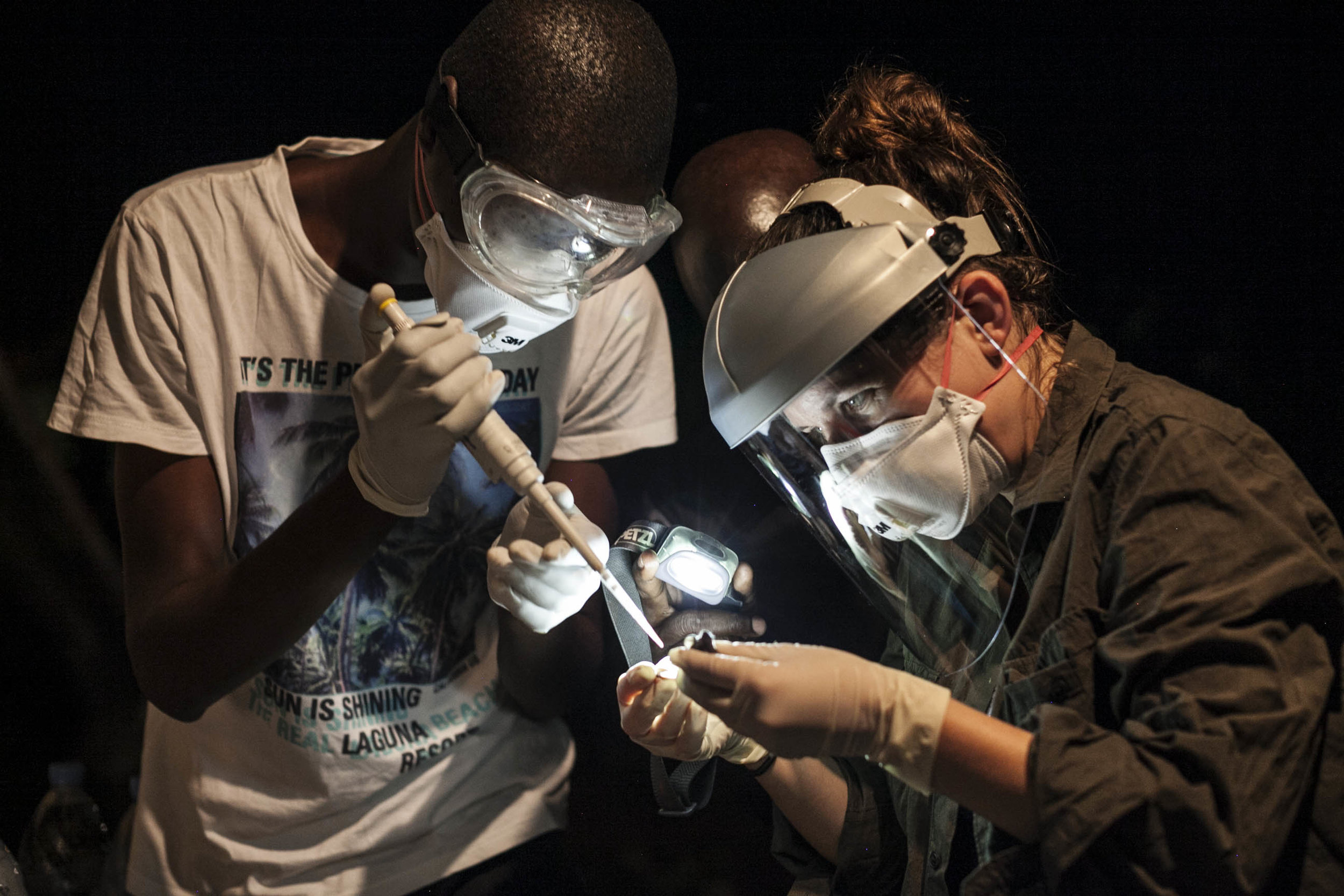

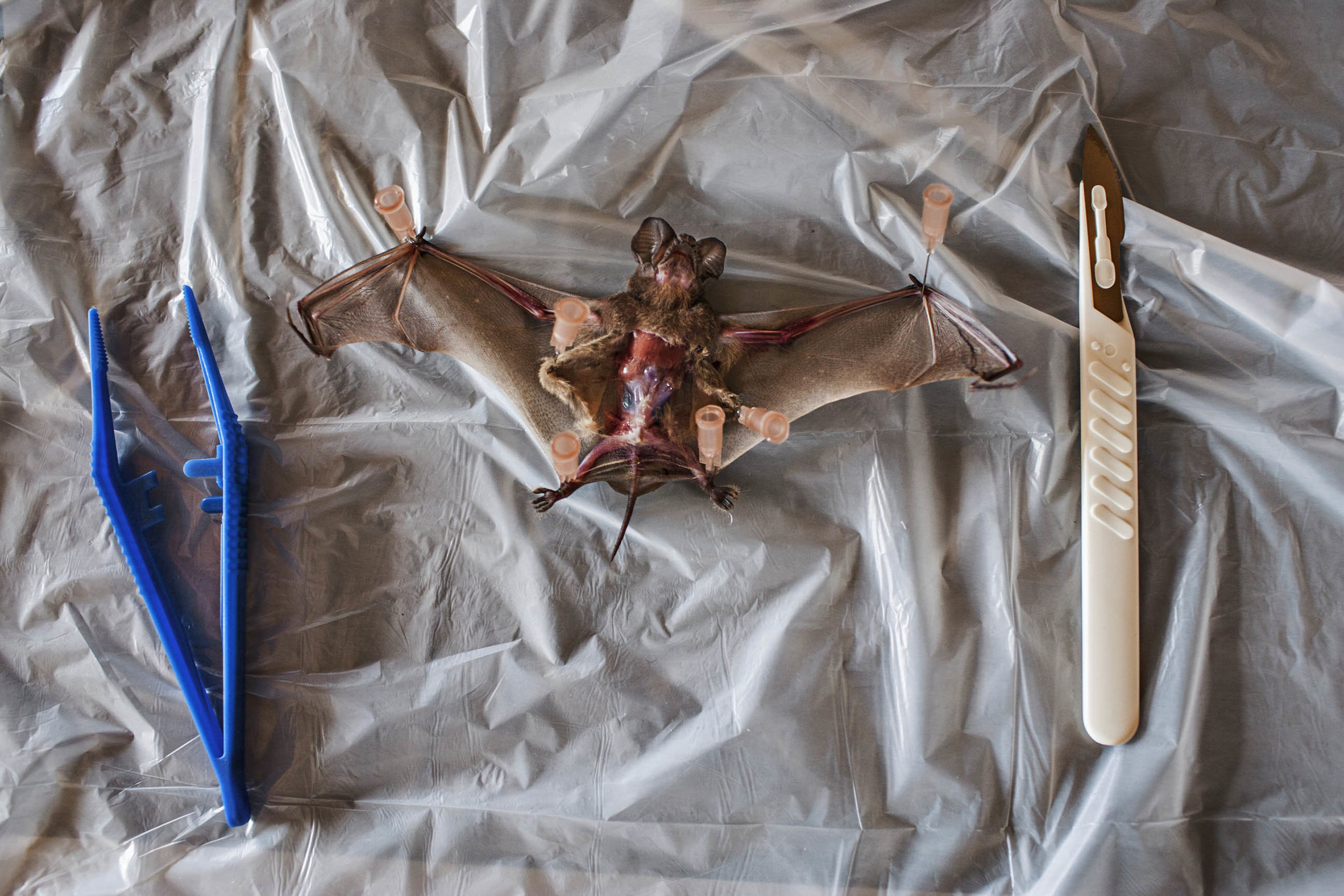

As the outbreak raged in West Africa, scientific researchers redoubled their efforts to identify the mysterious source of the virus. While bats are the main suspect, their status as the host of the virus had never been empirically confirmed. Dr. Fabian Leendertz, a German disease ecologist and veterinarian, lead a team of researchers to Meliandou where they began to look for clues as to how the virus emerged. On the outskirts of the village, Leendertz noticed a large hollow tree in which a large colony of Angola free tailed insect bats recently lived. Village children often played among the trees massive roots. He came to suspect that these small insect bats, which had never before been examined, might be the reservoir host of the lethal virus. His team began to survey and test these bats in areas throughout West Africa. While his interest in the insect bats was based on reasonable suspicion, in the end, the extracted samples did not yield proof of the virus.

While infection rates in West Africa have been dramatically reduced in recent months, the reservoir host continues to lurk in the shadows. With little known about why and how the virus spills over from the animal world into people, the prospect of future outbreaks remains inevitable.

Publications

Seeking the Source of Ebola, National Geographic Magazine

Awards

World Press Photo, First Prize - General News Stories, 2015